The Making of the Cellular Jail

By :

Pronob Kumar Sircar, writer of this research-based blog is an ethno-historian based at Port Blair

September 20, 2022

The history of our freedom struggle is replete with acts of courage, sacrifice, and dedication to the cause of freedom. The heroes of our freedom struggle came from every nook and corner of the country. They did not speak one language and they did not belong to one region or one caste. An intense love for their country and a keen desire to see it free was their common goal. The walls of Cellular Jail were accustomed to witnessing all these along with the unspoken inhuman tortures, sufferings, and extreme sacrifices. The undaunted spirit was beyond our imagination. Nothing could deter them from their committed task; neither money nor the tearful affection of their family members. The jail became a synonym for ‘black terror’; and the ‘imprisonment in the Cellular Jail’ came to be notorious as ‘Kalapani ki Saza’. Since the Cellular Jail is sanctified by the dust of the martyrs’ feet and their sweat and blood, it not only evokes interest and curiosity in the minds of every Indian but also becomes a holy place of pilgrimage or ‘Mukti Teertha’ in the present Indian consciousness.

Recommendation by Lyall and Lethbridge

A report on the working of the Penal Settlement of Port Blair by Sir Charles James Lyall of Bengal Civil Service and Surgeon Major Alfred Swain Lethbridge, Inspector General of Jails, Bengal dated 26th April 1890 submitted to the Secretary to the Government of India, Home Department mentioned in detail about the situation and difficulties pertaining to the penal settlement and prisoners in the Andamans. Their observation report became a basis for the authority to consider the construction of a concrete jail at Port Blair.

At point no. 12 of the report, Lyall and Lethbridge mention:

“Our next recommendation for making the earlier stages of imprisonment in the settlement more penal is that there should be a preliminary stage of separate confinement in cells. In the British and other European prison systems this preliminary stage has been worked for many years with the greatest success, and it is now considered essential in the management of jails where prisoners sentenced to penal servitude are first received.” Further, they write, “The close confinement of prisoners for long period in the Madras cellular jails and in one of the jails in Bengal (Midnapur) has shown that there is no reason to fear any deterioration in health either mentally or physically.”

Thus, this mentioning of them elucidates the fact that there was not only thought for security but other concerns too. Lyall and Lethbridge had observed the great loss of health among the prisoners and a large number of admission to hospitals from wounds and ulcers.

Further, they say:

“To enable the authorities to carry out this system, a cellular jail containing at least 600 cells should be constructed without delay”.

Initially, they served the thought to make the jail in Viper but some difficulties with it they highlighted in a separate appendix. Further, they suggested a well-raised inland non-malarious site at Port Blair. The option for selecting a site at Aberdeen was also in place. The local officers suggested Lyall and Lethbridge about the reclaimed land on Viper for construction of the new jail but insufficient space was observed in response.

Lyall and Lethbridge laid down some technical suggestions:

“The plan of cells that we would recommend is that adopted in the Madras close prisons. The buildings would be well raised, and should, if possible be two storied. The doors of the cells should face the northeast and should be protected by a verandah running along the whole length of the building. The entrance to each cell should be protected by iron-grated doors and the locks removed from within the reach of the prisoners in the manner adopted in the cells at Viper”.

The advantages claimed for this system of preliminary confinement, placed in the report were:

- Its great effect is as a deterrent punishment.

- The opportunity affords for studying the character of each individual prisoner and coercing the lawless spirits who have known no control.

- The improvement will secure the discipline and work of the prisoners in the Settlement when they know that they will be sent back to separate confinement if they give trouble. Instead of giving long sentences in the chain gang which can be evaded by going to the hospital, Settlement Officers would use the cells as a punishment for shorter periods and far more effectively.

- Preliminary confinement would be an excellent means of acclimatising prisoners without exposing them to the weather. Here also the health of the prisoners could be noted with accuracy, and their subsequent selection for special work could be made easier.

- In this stage, it will be easy to teach educated prisoners the Roman character, and so increase the number of prisoners qualified for work as writers.

- It will enable the authorities to dispense with the use of fetters on the first arrival or as a punishment. This in our opinion is a matter of considerable importance in a climate where the slightest abrasion has a tendency to fester and to pass rapidly into the stage of severe ulceration. The great loss of health and a large number of admissions to hospitals from wounds and ulcers will be noticed in the medical portion of this report.

In the report, it was clearly insisted that the life of a convict in the Andamans should be more penal in character. On basis of the report (approved vide letter no. 689 dated 29th July 1893), finally, it was decided to construct a jail that further came to be known as Cellular Jail. For the construction of the jail, two possible sites in the settlement were topographically surveyed. The first site was situated between Pahargaon and Protheroepur while the other site which was finalized, was at Atlanta Point in Aberdeen. On basis of the settlement order no. 423 dated 13th September 1893 issued by Colonel Norman McLoed Thomas Horsford, IA the construction was started in October 1896. Mr. W.G. MacQuillen was the sub-engineer then. About 600 convicts chiefly from Viper, Navy Bay, Phoenix Bay, Birchgunj, and Dundas Point were engaged in the work. Some of the building materials were brought in from Burma. The lime used in the mortar was obtained by burning raw corals which were collected from the innumerable coral reefs. Bricks were brought from the kilns situated at Dundas Point, Navy Bay, and other places on the islands. About the importance of its location, G. H. Turner 1897 mentioned:

“At Aberdeen, the new Cellular Jail in course of construction is the most auspicious landmark on entering the harbor. It is built on a hill some sixty feet above the sea level.”

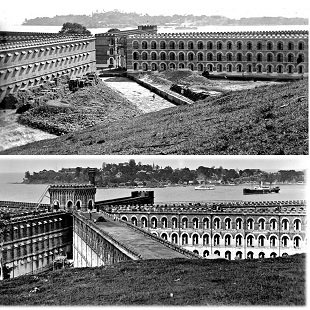

Cellular Jail during its construction

Eventually, the construction work was completed in 1906. The Viper Jail at the other end subsequently had to be closed on 1st February 1907. In the first year, 138 cells were constructed only in the wing 1 and 2; but in 1905-06, the total number of constructed cells of all the wings increased to 663 having 78 in Wing1, 60 in Wing2, 126 in Wing3, 105 in Wing4, 105 in Wing5, 126 in Wing6 and 63 in Wing7. In the year 1909, additional 30 cells were constructed in Wing3. The construction work was witnessed and supervised by different Chief Commissioners beginning from Col. Norman McLoed Thomas Horsford (1892-1894) to Col. Sir Richard Carnard Temple (1894-1903) to F.E. Tuson (1903-1904) to William Rudolf Henry Merk (1904-1906) to Lt. Col. Herbert Arrott Browning (1906-1913).

Built in the shape of a gigantic starfish with seven massive tentacles-like wings fanning out from a central watch tower, the Cellular Jail housed seven three-story wings, from which, now only three remain. The Cellular Jail earned its name for its uniformed isolated cells. All the wings were not equal in length. A panopticon idea was carefully adopted in the design of the Cellular Jail, and as a result of this, the British rulers kept effective surveillance on a large number of inmates with less number of guards. The seven wings intersected at a central guard tower. The wings were engineered in such a way that the face of a cell in a wing saw the back of cells in the opposite wing. For this technical reason, communication between the prisoners was impossible. For instance, the Savarkar brothers interned in the same jail and did not see each other for nine long months before a coincidence. Wing 3 stood with the comparatively maximum number of cells. The size of each cell was thirteen and a half feet by seven feet. Each cell was well secured with a sturdy iron bolt and lock on a rectangular groove on the outside of the cell wall a few inches away from the door. A double-storied building on the left side near the entrance of the jail was also constructed to be used as the jail hospital. Near the compound wall at the right side of the main entrance were the gallows capable of hanging three convicts at a time with a door in the outer compound wall to carry out the corpses. Adjacent to the gallows was the kitchen for Muslim and Hindu sections. The wooden double-story administrative block at the main entrance was visible from the outside and is bound on either side by two turrets with stairs leading to the first floor.

During the year 1906-07, the Cellular Jail although completed, was further improved with provisions made for worksheds in the exercise yards and a carpet factory was erected in one of them. A mortuary and a well were built outside the jail. The hill in front of the jail was leveled off.

Captain P.F. Browne Superintendent of the Central Jail, Jubbulpore, was appointed Superintendent of the Cellular Jail and Female Jail on the 3rd January 1907. At the same time, he was appointed as Civil Surgeon, Port Blair.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, the Swadeshi movement, the partition of Bengal, and the emergence of extremist groups in the country led to the adoption of violent methods. Revolutionary activities grew up in Maharashtra, Bengal, Punjab, and other provinces. The Anushilan Samiti was the most active organization which played a prominent role in planning and executing the attacks on the British officers with its headquarters in Bengal and many other parts of the country. Arms were collected and bombs were manufactured by the members of the Anushilan Samiti. From 1906, a secret wing under Barin, Upen, Ullaskar, and others began working in a garden house in Manicktola in the eastern suburb of Calcutta. This activist group of revolutionaries came to be known as the ‘Jugantar’ group. Their slogan ‘Vande Mataram’ taken from Bankim Chandra’s ‘Anand Math’ thrilled the revolutionaries. Such were these organizations which built their young workers ‘thunderbolts’. Among these workers, were Barindra Kumar Ghosh (younger brother of Sri Aurobindo), Ullaskar Dutt, and Bhupendra Nath Dutt (younger brother of Swami Vivekananda). The prominent figures of Indian nationalism Lokmanya Tilak, Surendranath Banerjee, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Madan Mohan Malviya, and Rabindranath Tagore were great admirers of the revolutionaries. As the freedom struggle spread to different parts of the country, batches of these firebrand freedom fighters were deported to the Andamans from time to time.

The political prisoners of the Manicktola Conspiracy Case or say Alipore Bomb Case after the Bomb incident of 30 April 1908, were the first batch to enter the newly built Cellular Jail. It was perhaps the first ‘criminal conspiracy’ of high magnitude hatched by the revolutionary youth to wage war against the British. The first batch of prisoners convicted in the case included Barindra Kumar Ghosh (for life), Ullaskar Dutt (for life), Upendranath Banerjee (for life), Hem Chandra Dass (for life), Indu Bhushan Roy (for 10 years), Bibhuti Bhusan Sircar (for 10 years), Hrishikesh Kanjilal, Sudhir Kumar Sircar, Abinash Chandra Bhattacharjee (for 7 years), and Birendra Chandra Sen (for 7 years). These political prisoners were brought to the Andamans by the vessel Maharaja, in December 1909, with the clear instruction to the Superintendent of the jail that they should be regarded as especially dangerous, and should not be allowed to work in the same gang with each other, nor with Bengali convicts looking to their large number, should not be employed in clerical work and as rule, they should be given hard gang labour. After his release from the Cellular Jail, Barindra Kumar Ghosh wrote his memoir The Tale of My Exile in 1922.

A few journalists (Hoti Lal Verma and Bauram Hari, Editors of Swaraj, an Urdu Weekly of Allahabad) convicted for seditious writing, were recommended to be confined in the Cellular Jail. Upendranath Benerjee and Hrishikesh Kanjilal were associated with the Jugantar Publication. Nand Gopal and Sham Dass Verma were also convicted for seditious writing in 1910 and Pandit Ram Charan Lal Sharma was the next after them.

Some of the patriots deported from 1909 onwards were repatriated in 1914 and the subsequent repatriation was due to the general declaration of amnesty on the occasion of the introduction of the new reforms under the Act of 1919. The dispatch of prisoners to the Andamans was suspended under a general decision adopted to abolish the penal system in the Andamans. On a few occasions, the Government of India formally resolved not to send political prisoners to the Andamans, but later on, it felt impelled to reverse the decision under compelling circumstances.

During the period 1909 -1938, the Cellular Jail – the Indian Bastille was replete with the presence of many other leading great personalities of the Indian freedom struggle. Among them were Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Ganesh Damodar Savarkar alias Babarao, Nani Gopal Mukherjee, Nand Kumar, Pulin Behari Das, Bhai Parmanand, Prithvi Singh Azad, Trailokyanath Chakravarty alias Maharaj, Ananta Singh, Pandit Ram Rakha, Mahavir Singh, Sachindra Nath Sanyal, Mohan Kishor Namadas, Mohit Moitra, and Baba Bhan Singh, and Batukeshwar Dutt, etc. The list is long and distinguished. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the doyen of the Indian revolutionaries, the ‘potential danger’ for the mighty British empire was convicted in the Second Nasik Conspiracy Case, brought to the Andamans in 1911 by vessel S. S. Maharaja with a badge of a sentence for fifty years around his neck, but he was repatriated in May 1921. The revolutionaries were convicted in different conspiracies including the Nasik Conspiracy Case (1909) and Khulna Conspiracy Case (1910), Second Nasik Conspiracy Case (1911), Rajindrapur Train Dacoity Case (1911), Gadar Party Revolution (1914), Shibpur- Nadia Action Case (1915), Assembly Bomb Case (1929), Lahore Conspiracy Case (1929-30), Chittagong Revolt (1930), Watson shooting Case (1932), Birbhum Conspiracy Case (1933), Midnapur Murder Case (1933) and many other cases.

The revolutionaries in Cellular Jail were not treated as political prisoners but as ‘seditionists’ or ‘anarchists’ and were treated worse than ordinary criminals. They were given class ‘D’ (Dangerous) or ‘PI’(Permanently Incarcerated). All kinds of torture ranging from engagement in backbreaking manual work, poor food, and non-medical aid to the hurling of abuses and flogging were a part of the routine behaviour of the jail authorities with the prisoners. The prisoners were employed in Cane and bamboo work; coconut and mustard oil mills; husking of coconuts; drying copra; making hooka shells; coir pounding; Sisal pounding; making of rope, carpet, and net; weaving towels; Coir and Sisal hemp mat making; cleaning mustard seeds; blanket mulling; gardening; hill cutting, cleaning drains and swamp filling (when necessary); and other miscellaneous works. Many of the prisoners hailed from Bhadralok families and were educated, but they were also employed in the severest tasks of coir pounding, rope making, and oil grinding on the Kolhu.

The revolutionaries spent a gruesome and torturous life in the Cellular Jail until they were released. Life in the Cellular Jail was so dreadful and precarious that in every moment, some horrible experience awaited even for the innocent. David Barry, the head overseer, and the jailor was cruel to the prisoners. Barin Ghosh and Savarkar mentioned the despotic address of David Barry who worked as a Jailor during 1905-1919. Khoyedad, an ex-prisoner, wearing the garb of a jail official strictly followed Barry in making the life of the prisoners most miserable. During the visit of Reginald Henry Craddock, a Home member in 1913, Nand Gopal lodged a complaint to him against David Barry for his inhuman behaviour. Mirza Khan, a miniature of Barry, was another cruel jail staff. The prisoners were not permitted to communicate with each other. All conversation was illegal and violative of the Barry rule. The sacred threads Janeu of the Hindu convicts were removed (Pandit Ram Rakha attained martyrdom in his fight for sake of it). Many of them either committed suicide or died of torture, in the midst of the endless tortures. Indu Bhushan Roy could not bear the humiliation and inhuman torture and he had to commit suicide out of exhaustion and frustration. The severest punishment in the jail was solitary confinement. During the visit of the Indian Jails Committee in 1919-20, the political prisoners submitted a Memorandum stating therein the cruel treatment to which they were subjected.

The conditions of political prisoners were summed up by Colonel Wedgewood, a member of the British parliament in an article published in the Daily Herald with the title ‘Hell on Earth-Life in the Andamans’. As an impact of it, questions were asked in the council of the Governor General of India. In May 1932, Sir John Anderson visited the islands and recommended the use of the formidable penal settlement in view of the relaxed discipline in the Indian jails. The Government of India decided to defer the implementation of the recommendations of the Indian Jails Committee regarding the abolition of the penal settlement. On 12 July 1932, Sir Samuel Hoare, the secretary of state for India, announced in the House of Commons his approval of the proposal of the Government of India to transfer to the Andamans one hundred convicted revolutionaries. The policy decision of sending political prisoners to the dreaded ‘Kalapani’ was strongly criticized by the public and press, as it was against the spirit of the report of the Indian Jails Committee, 1919 (Cardew Committee) and their declared policy of abolishing the punishment of transportation. The monstrous gates of the Cellular Jail were again waiting for the political prisoners to swallow them. A batch of twenty-five political prisoners from Bengal including those convicted in the Chittagong Armoury Raid Case was the first batch to be transferred to the Andamans on 15 August 1932. Some more political prisoners were sent thereafter in 1932; and by the time of the hunger Strike of 1933, near about hundred political prisoners were incarcerated in the Cellular Jail.

Nand Gopal and few others had to lead the first Hunger Strike began in 1933 in participation of the revolutionaries. The Chief Commissioner said, “I shall not budge an inch. Let their dead bodies be floating on the ocean”. During the strike three patriots Mahavir Singh, Mohit Moitra and Mohan Kishor Namadas died. They were under forced feeding. Rabindranath Tagore became emotionally upset and remarked in his telegram, “Your motherland will never forget her full blown flowers”. The strike was called off on 26th June 1933, the 46th day after its commencement, with few relaxation offered to the prisoners. A Handwritten magazine ‘CALL’ which had its English and vernacular sections was issued to them. After the first hunger strike, the political prisoners tried to draw attention of the British Government to their repeated representation and uniform classification. The representation was submitted to the Home Minister.

In 1934, one of the political prisoners deported in 1932 namely Sudhendu Chandra Dam, Son of Ananda Chandra Dam from Chandrapur, Nakari of Bengal attempted attack on the Jail Superintendent.

Sir Henry Craik, Home member visited the jail in April 1936, and the political prisoners submitted a charter of demand to him. But after his return he described to a group of Simla journalists that Andaman was a ‘prisoners’ paradise’. There was a strong protest against the statement of Sir Henry Craik and the members of the Legislative Assembly insisted that some of them be sent to the Andamans to assess the truth. The Government accordingly sent Raizada Hansraj and Sir Mohammed Yamin Khan to the Andamans. After their return they wrote in their report that Andaman was not a ‘paradise’ but a “prisoners’ hell”. They observed the facts of repression and oppression meted out to the patriots by the British in the Cellular Jail. A Memorandum dated 13th October 1936, which was signed by 239 political prisoners expressing in detail their conditions. They submitted another memorandum dated 18th October 1936 with more facts to refute Craik’s false statement.

On 24 July 1937 they started the second mass hunger strike. Their political demands gave a new impetus to the democratic movements in other jails and camps. The political prisoners at Alipore, Deoli, Berhampur started hunger strike in support of their compatriots in the Cellular Jail. Thus, the whole country rallied behind them. In reality it had become a mass movement for the repeal of repressive laws, repatriation of the exiled prisoners, release of political prisoners and extension of civil liberties. Thus the revolutionary prisoners transformed the Cellular Jail from a place of suffering and sacrifice into an active centre of freedom struggle. Eventually, as a result of intervention by national leaders, the hunger strike was called off on 28 August 1937, and repatriation started on 22 September 1937.

The memoirs of Barindra Kumar Ghosh entitled The Tale of My Exile (1922) translated from Deepantorer Kotha (Bengali), Upendranath Bandopadhyay’s ‘Nirvasiter Atmakatha’ (in Bengali), Sachindra Nath Sanyal's book Bandi Jeevan (A Life of Captivity, 1922), auto-biographies of Ram Singh, Prithvi Singh Azad and Bhai Parmanand, Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna’s Jeevan Sangram, Bejoy Kumar Sinha’s In Andamans – the Indian Bastille, Shailesh Dey’s Ami Subhash Bolchhi, (Bengali in 1976), Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s Majhi Janep (in Marathi) along with its English translation The Story of My Transportation for Life (1950) by Prof. V.N. Naik and the Hindi translation Ajanm Karavas (1966) narrate in detail the poignant life, agonizing routine, the various methods of torture and sacrifice of the prisoners in the Cellular Jail. Ullaskar Dutt deported in 1909 also wrote his memoirs Twelve Years of Prison Life. Some other revolutionaries who were imprisoned from 1915 to 1921 have also written about their experiences and the jail system. Excluding few of these revolutionaries who are well known through their published memoirs, a majority of the revolutionaries, for the rest part of the life, had to live in anonymity, desertion and poverty. For evidential instance Nagendra Nath Dey (Bathua Action and Conspiracy Case) and Saroj Kanti Guha (Chittagong Armoury Raid Case), incarcerated in the Cellular Jail in 1932-38, after repatriation, had to live in utter poverty with no livelihood support to live with. Saroj Kanti Guha, an associate of Master Surya Sen accompanied by another revolutionary Romen Bhowmick, killed Mr. Durno, the then District Magistrate of Dhaka on 28 October 1931. The story of his bravery has been less known and less spoken but available in page no. 282 of Shailesh De’s Ami Subhash Bolchhi written in Bangla language. After killing of Magistrate Durno, Saroj Guha and other revolutionaries disappeared from the scene and remained out of the catch. The frustrated British arrested a large number of Dhaka residents on ground of suspicion. To protest against the arrest and torture of the innocent people Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose arrived but he was not permitted to enter the Dhaka and was arrested at Narayangunj Railway Station on 7 November 1931. He was released and sent back by a steamer from Chandpur (Ananda Bazaar dated 08-11-1931). Later, Saroj Guha was arrested and transported to Andamans. He was made blind of one eye by torture in the Cellular Jail. He came to Andamans during 1976-77 as a member of the group of Freedom Fighters.

The book of Sailesh Dey, Ami Subhash Bolchhi (I am Subhash Speaking), written in 1968 is most illuminating. Amalendu Ghosh, while writing the preface to this work, rated this thousand page tome as the well-documented detailed history of Indian armed nationalism. Dey described the inspiring tale of all the armed nationalists in a moving fashion, while telling the story of Subhas Chandra Bose. Khudiram, Prafulla Chaki, Surya Sen, Rashbehari Bose, Bhagat Singh, Dundee Khan, all come to life in the pages of this book. The most noted aspect of this work is that it focused on the patriotic episodes untold in the mainstream history books, such as the revolt of the Indian soldiers led by Dundee Khan in Singapore during the First World War or the insurrection of the fourth Madras Coastal guards in course of the second World War in which nine young soldiers lost their lives. In the last part of his work, Dey clearly stated that the accounts of many events of the Indian Freedom Struggle were deliberately suppressed by the Government of India. It was the duty of the patriotic citizens like him to make the public hear the voice of the neglected armed nationalists.

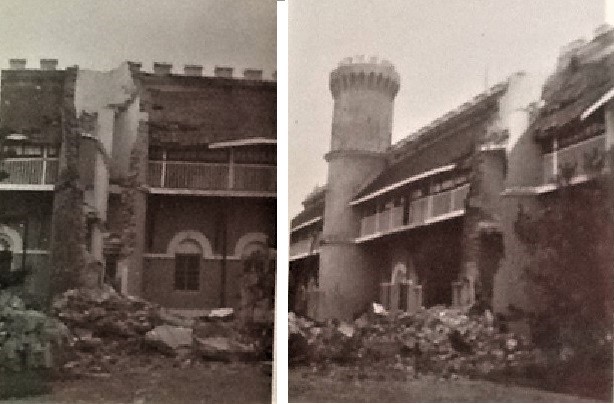

Cellular Jail in 1941 Earth Quake

The Cellular Jail with the passage of time, suffered many ravages brought about nature and man. The earthquake of 1941 and the Japanese invaders have caused substantial damage to the building. The Central Tower originally square in shape, after the damage, was replaced with a new tower of round shape. Four of the seven wings were grounded, two by the Japanese (they used the bricks in construction of bunkers and in other works) and two have made way for the Govind Ballabh Pant Hospital. The wing 1, 6 and 7 and the watch tower have been preserved.

Cellular Jail damaged in 1941 earthquake

The Cellular Jail during Japanese occupation

The Andaman history has travelled a long way from ‘barracks’ of 1857-58 mutineers to the ‘bricked jail’ of political prisoners of 1932-38. The colossal Cellular Jail has witnessed the torture and suffering of the prisoners of not only the British Raj but also of the Japanese occupation.

During the Second World War, right after the Japanese force arrived in the islands in March 1942, they released all the prisoners then incarcerated in the Cellular Jail. Later on, they used the jail with a strange concept. They imprisoned many of the citizens using the jail cells as ‘confession rooms’ through a series of varied tortures. A large number of the reputed local residents with a majority of the members of Indian Independence League (IIL) and Indian National Army (INA) were incarcerated in the Cellular Jail, on false charges of espionage. Muthuswamy Naidu died of torture in the Cellular Jail on 26 January 1943 being the first islander to die in the Cellular Jail during the Japanese occupation. A series of mass-killing began with the massacre of seven reputed imprisoned islanders namely Narayan Rao, Itter Singh, Surendra Nath Nag, Abdul Khaliq, Suba Khan, Chotey Singh and Gopal Krishna at Dugonabad on 30 March 1943. This was the First Spy Case also known as Narayan Rao Spy Case. In the Second Spy Case or say Dr. Diwan Singh Spy Case, the Imperial Japanese Force arrested the residents particularly the members of the IIL and INA and confined all of them in the cells of the Cellular Jail. These batch of prisoners included Dr. Diwan Singh, Bachan Singh and the members who were later massacred at Homfraygunj on 30 January 1944.

The Japanese forces in the Andamans appeared to be far more cruel and barbaric than the British through their mass-killing and inhuman torture as experienced and expressed by the islanders. They in the Cellular Jail, in addition to the suspected citizens, arrested their mothers, wives, sisters and daughters and tortured them to the extent unspeakable. After Dr. Diwan Singh with his colleague Bachan Singh was arrested on 27th October 1943, Kesar Kaur and many other female members were also arrested only to put emotional pressure on their imprisoned family members particularly on Dr. Diwan Singh. N. Iqbal Singh on basis of what the co-prisoners stated, described about how Dr. Diwan Singh had to undergo the various treatments with strategies of the Japs being changed every day. He wrote –

“Now the Japanese and their Indian stooges thought of a new plan. They arrested some women including one Kesar Kaur, most of whose husbands were already in the jail being tortured. These women were told to go and persuade Dr. Diwan Singh to confess, and if they succeeded in doing so, their husbands would be released. When they were taken to Dr. Diwan Singh, he told them, You don’t know how treacherous these Japanese are. I am undergoing all this torture and suffering in the interest of your husbands and others in this island. Were I to ‘confess’ to this false charge, not one of your men-folk will be spared. They will all be put to death.”

The Japanese failed to gain their goal through these women, and tortured these women too including Kesar Kaur. One form of torture, perhaps the worst of its kind, consisted of the naked body of a person being put in a kind of stock made of steel, in which his feet and arms, spread wide, were so tightly manacled that he could not move. He was then ruthlessly beaten. He could not even scream, nor turn his lacerated body. He repeatedly fell and fainted, whereupon his tormentors would wait and again ask him to ‘confess’. If he still persisted in his refusal, which most people and Dr. Diwan Singh in particular did, they would again be put him in the stock and thrust red hot nails into the tips of his fingers and toes. Naturally the tortured person would again faint. They would wait for the person regaining consciousness to be asked once again to admit that he committed a crime. Another refusal, and then the flesh on his arms and legs would be pierced with sharp knives and salt to be sprinkled on the cuts and wounds. At times the stock was so tightly pressed that every bone in the sufferer’s body cracked. Another variation of the punishment in the stock was that they would tie up the person in it and apply burning candles to the parts of the body, including the genitals. And when the unfortunate and hapless person, being subjected to this form of torture, howled in pain, the torturing group would shriek with laughter. Some other varieties of the torture by the Japanese were, water treatment, electric treatment, and sitting treatment, etc; and Dr. Diwan Singh had to bear almost all these forms of the torture. Kesar Kaur was again asked to give her statement that Dr. Diwan Singh was a British Spy. On the other end Dr. Diwan Singh, who despite the extreme torture was in no mood to accept the crime that he did not commit. Kesar Kaur on her refusal was beaten and tortured to the extent she fell unconscious again and again. She insisted on repeating, “I will not tell a lie, even if you beat me to death. Diwan Singh is like a father to me.” Kesar Kaur’s husband Banta Singh was also tortured but he too remained true to his soul. The irritated and frustrated Japanese, on finding no strong witness, were inflicting every kind of torture that they could think of on Dr. Diwan Singh.

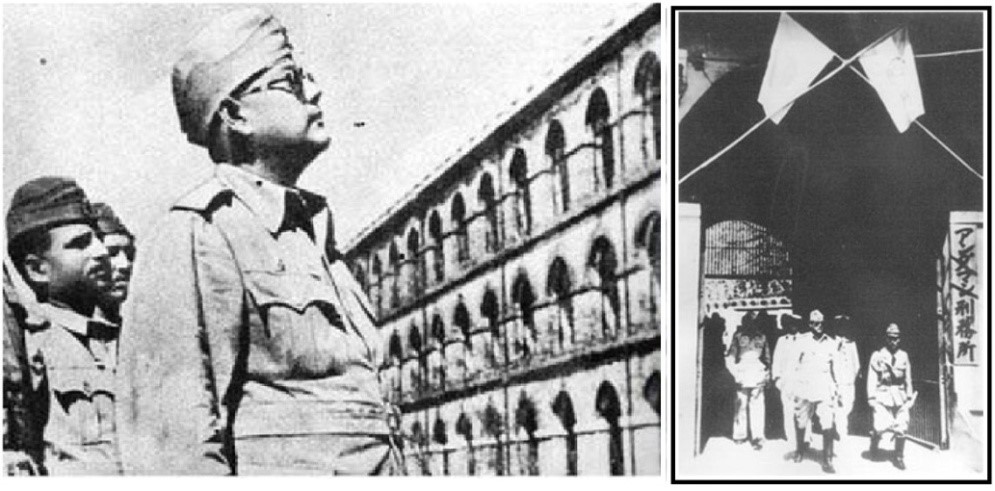

Meanwhile, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose arrived in the Andamans on 29 December 1943, received by Admiral Ishikawa. He hoisted the first Indian National Flag at Port Blair on the next day and visited the Cellular Jail. During his entire visit to the Andamans, he was always surrounded and escorted by the Japanese officials and soldiers. He visited Cellular Jail but was intentionally not taken to the Wing No 6 where the local citizens, members of the Indian National Army (INA) and Indian Independence League (IIL) including the President of IIL Dr. Diwan Singh, were incarcerated facing the barbaric treatment of the Japanese.

Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose during his visit to Cellular Jail on 30 December 1943

Netaji went back and with him the hope of relief went back. Dr. Diwan Singh and other had to continue to bear the series of torture. The irritated Japanese finally picked up another arrow of torture from their quiver. They decided to cut his beard and the hair of the head. Dr. Diwan Singh for the first time became emotional and said,

“You can lop off my head and kill me. I will accept that punishment cheerfully, but don’t commit this sacrilege. Despite his protest with his full energy, he failed to stop the cruel Japanese in doing so.”

Hitherto Dr. Diwan Singh became too weak to bear further tortures and eventually during a course of torture, he left this world without breaking his spirit on 14 January 1944. An eye witness stated about his condition he saw at his last time, that his hands and his feet and the rest of the body bore signs of having been burnt. His arms seemed to have been lacerated by sharp knives and wounds were full of puss. The hairs on his head and his beard seemed to have been forcibly pulled out. It appeared as though his eyes too had been gouged. His spine had been broken as a result of continuous beating. Because his flesh had been burnt at many places, most of his bones could be seen and so could be the charred bits of his flesh that were hanging. His body was cremated at Junglighat. The noble life and supreme sacrifice of the eminent freedom fighter Martyr Dr. Diwan Singh Kalepani became a source of courage and inspiration to every Indian as well as every islander of today and the future.

Just one month after Netaji’s return from the Andamans, forty-four persons, mostly from IIL and INA who were imprisoned in the Cellular Jail, were taken out from the main gate of the Cellular Jail in few trucks and these innocent citizens were brutally massacred at Homfraygunj on 30 January 1944 (on the day of Basant Panchami).

More than 600 persons including females were arrested and imprisoned in the Cellular Jail. Two of the members Master Moti Ram and Faizul Hussain were released from the jail on 19 November 1943 after injecting poisonous injection in them.

Martyrs of Cellular Jail during Japanese Occupation

The Andaman history is incomplete without mentioning of the martyrdom of Dr. Diwan Singh Kalepani. The other martyrs who died of inhuman torture in the Cellular Jail during the period 1943-1945, were Hari Kishen (died on 15-01-1944), Bhagwan Dass (died on 20-01-1944), Bhikham Singh (died on 30-11-1943), Bakshish Singh (died on 20-01-1944), Baldeo Sahai (June 1944), Charanji Lal (died on 21-01-1944), Dhanakdhari Lal (died on 26-01-1945), Farman Shah (died on 25-01-1944), Gulab Khan (died on 21-01-1944), Hari Kishen (died on 15-01-1944), Khan Sahib Nawab Ali (died on 23-07-1945), Lall Singh (died on 23-01-1944), Niranjan Lal (died on 28-11-1944), Patti Ram (died on 22-01-1944), Santa Singh (died on 24-01-1944), Sangra Singh (died on 17-01-1944), Singhra Singh (died on 25-01-1944) and many others.

The Imprisonment and Torture on False Charges of Espionage

After the martyrdom of Dr. Diwan Singh, Ramakrishna and Bhagwan Singh (grandson of Mangal Singh Dogra of the first war of independence 1857) were also arrested and tortured. In addition to some names already mentioned, the residents including the members of the IIL, incarcerated in the Cellular Jail, were Ram Swaroop (arrested in November 1943 by the Japanese and on 07-10-1945 by the Allied British Force), Guru Moorthy (arrested on 10 November 1944), Lachman Singh (grandson of Mangal Singh Dogra of the first war of independence 1857, arrested in January 1944), Abdul Gafoor (arrested in November 1943 and released after a month to be re-arrested in July 1944), Brojendro Lall (arrested in November 1943, sentenced for three years on 30 January 1944 with Convict No. 622), Ram Gobind (arrested in November 1943, sentenced for fifteen years on 30 January 1944 with Convict No. 620), Het Ram (arrested on 15 January 1944 and sentenced for fifteen years on 30 January 1944), Sardar Khan (arrested in November 1943 and released after a month but re-arrested in June 1944), Bijay Bahadur (arrested twice by the Japanese force and then his third arrest was made by the British on their re-occupation to produce before the War Crime Trial court at the Cellular Jail), Lala Niranjan Lall (arrested twice by the Japanese), P. Arumugam (arrested after Netaji’s departure), Master Ram Narayan (arrested in Oct 1943 and July 1944), S. Paras Ram (arrested in August 1944), Kristo Mohan Lall Shah (arrested at the time of mass arrest of November 1943), Sakar Kandi (arrested in November 1943), Sebastin Pinto (arrested in November 1943), Lala Brij Lal Dua (arrested within a week of the departure of Netaji and re-arrested in July 1945), Ram Phal (arrested in Sept 1944 and hospitalized due to severe torture), Memeveetil Mohammed (arrested in Nov 1943 and provided with Convict No. 624 sentenced for ten years), Pando (arrested and sentenced after Homfraygunj massacre for three years imprisonment), Nassar Mullah (arrested and sentenced after Homfraygunj massacre for three years imprisonment with providing of Convict No. 619), Labh Singh (arrested and sentenced after Homfraygunj massacre for three years imprisonment with providing of Convict No. 631), Naseeb Singh (arrested and sentenced on 30-01-1944 after Homfraygunj massacre for three years imprisonment), Birshah, Y. Venkat Ratnam, P.R. Ghose, Sukh Ram, Awaldeem (arrested in July 1944), Radha Krishna (arrested in April 1944), and Lachman Dass. In addition to these members, many other persons were imprisoned in the Cellular Jail with the false charges under the mass arrest in January 1944. These prominent persons were Autam Lachman Dass, Pyare Mohan, S.R. Bose, Narayan Swamy, Shore Chand, Master Abdus Subhan, Pt. Ram Bhore, Manohar Singh, Sardar Kundan Singh, Santook Singh, Pandit Ralla Ram, T.S. Guruswamy, D. Sirikishen, Kesar Dass, Bhagat Singh, Jeevan Singh, Gulam Hussain Shah, Ram Singh, Krishna Nair K, Pathan Khan and Ram Dass.

Ichawati Nag and Ruth Meshack, President and Secretary of the Women’s Wing of the Indian Independence League respectively, and many other female members of the IIL including Savitri Bai, Khairun Nisa and Kishen Dei (incarcerated in the Cellular Jail for six times) were imprisoned facing inhuman torture in the Cellular Jail during the Japanese occupation.

Durga Parshad, a prominent figure of the islands, was also arrested and in the prison he had to face barbaric treatment of the Japanese force. He was released after a fortnight, after the formation of Azad Hind Government. He continued to work and he was again arrested in the month of April 1944 to face again the barbaric torture of the Japaneses and the Indian Military Force to confess being a British spy, but he on all occasions denied the false charges. The trial, the torture and the denial went simultaneously with him and he was again interned in jail, and received his release order on 14 September 1945, owing to the Japanese surrender. He was again arrested by the British force on their re-occupation, on the charges of waging war against the British through the organ of IIL. He had to face the War Crime Trial conducted in the Cellular Jail.

Sardar Bunta Singh with his brothers joined the IIL. The Japanese force arrested and interned him in the Cellular Jail and allotted him Convict No. 623. When he was arrested his brothers Dulip Singh, Gopal Singh and Gajjan Singh and sister-in-law Kesar Kaur were already imprisoned in the Cellular Jail. He was severely tortured to confess being British Spy. On 30 January 1944 after the Homfraygunj massacre the Japanese sentenced for him ten years of imprisonment. He was released on 14 September 1945, after the Japanese surrendered.

The prominent INA members who were incarcerated and tortured in the Cellular Jail on false charges of British espionage by the Japanese, were Aftab Ali (son of Akbar Ali), Brij Behari Lall (son of Kunj Behari Lall), R. Shyam Nath (son of Ram Nath), Brij Lall (son of Kailash Chandra Dass), Ratindra Lall (son of Mohan Lall), Denger Singh (son of Hanuman Singh), H. Govind Ram (son of Het Ram), V. P. Kashyap (son of Bhagwan Singh), Ram Moorthy (son of Dariya Gonda), Abdul Jabbar (son of Abdus Subhan), B. D. Malhotra (son of Relumal), I. Sadiq Ali (son of Iddo Choudhary), Rahmatullah (son of Hamidullah), M. Abdul Qader (son of Abdul Majid), Mohammed Baksh (son of Allah Baksh), Hira Lall alias Hiru, Ram Dulare (son of Mohan), Jageshwar Lall (son of Lala Amrit Lal), Har Kishen Lall (son of Lala Amrit Lal), Ram Chander Rao (son of Govind Rao), Usman Ali (son of Abdul), L. Hari Ram (son of Lodi Ram), Mahmood Ali (son of Jafar Ali), V. Siri Krishna (son of Venket Giri), Naga Lingam (son of P. Arumugam), Abdul Ahmed (son of Roshan), P. Ram Lall (son of Prasadi), Jag Narayan (son of Jai Narayan), Sham Singh (son of Durga Singh), Mahmood Ali, Kadar Baksh (son of Allah Baksh), and many other unsung heroes. Interestingly, the prominent INA leader L. Paras Ram (son of Lodi Ram) was enlisted by the Japanese but in his place another person having the same name was arrested by mistake.

The Massacres or Genocides Operated from Cellular Jail

After the mass killing of seven reputed citizens, and forty-four INA and IIL members in the Homfraygunj massacre on false charges of espionage, the round up at Tarmugli and killing of fishermen, etc. the Japanese tendency of mass killing did not subside. Being frustrated by the shortage of food and sinking of the Japanese ships, the Japanese decided to reduce not only the suspected spies but the general population of the Andamans. More than 200 residents including Saudagar, Govardhan, Lall Singh, Brij Lall Dua, Dhani Ram, Sepoy Karnail Singh (4096), Sepoy Lal Khan (3828), were imprisoned in the jail, and same day on 4 August 1945 they were taken by the steamer Akbar and two Light Transport Crafts to a deserted island – Havelock Island. All of them died of forced drowning by the Japanese except few persons who were later rescued. Two of them were Saudagar and Govardhan. Few days after, hundreds of the residents were taken to an unknown place at Garacharama and killed. Hundreds of the residents were massacred at an uninhabited island - Tarmugli Island. Then, the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender saved the lives of another group of residents, selected for the next round up in the end of August 1945. There is a narrative of an old renowned resident of the time that another group of about 325 people were made ready for the round up, but soon the news of Japanese surrender came in, and the Japanese released them forthwith. It is also learnt that a batch of people was housed in a bunker to be killed by poisonous gas after closing the mouth of the bunker, but they were killed or not and where it occurred, nobody knows.

Old column in memory of the freedom fighters interned in Cellular Jail, where Dr. Rajendra Prasad placed floral wreath in 1954

The jail was severely damaged due to the earth quake of 1941 and bombardment by the Japanese in 1942. Two of its wings were put down by the Japanese in order to obtain an easy supply of bricks to build trenches and pill-boxes. (File No. 41-1/68-House). A letter from Littleworth dated 20th October 1945 reveals that in the Wing 2 and 5, about 200 Japanese Prisioners of War were accommodated for that time being.

Many batches of the refugees after 1950 were also accommodated in the cells of the Cellular Jail. In the subsequent years, the jail wings were used in different other ways. As per a file note dated 29th August 1968, during this period one wing of the Cellular Jail consisting of 106 cells was being used as jail, the second wing with 126 cells as Medical Stores and the third wing of 52 cells as Bachelors Mess (File-41-1/68-House; archives H 901).

When came in news about the sick plan to dismantle the remaining three wings of the historic Cellular Jail, on 24 April 1967, Shri B.L. Banerjee and 300 other freedom fighters presented a Memorandum to the Prime Minister of India praying for the conversion of the Cellular Jail into a National Monument. The attempt to demolition of Cellular Jail was immediately stopped after the visit and instruction of the then Home Minister to the Andamans Islands in November 1967.

Meanwhile when came to know about the Government’s plan to dismantle the remaining three wings of the historic Cellular Jail, a letter was written by a former revolutionary prisoner of the Cellular Jail, with his deep pain and anger,

“We do not know on whose initiative the demolition of the Cellular Jail was begun. We revolutionaries who were incarcerated in the Cellular Jail intervened. We felt strongly that this symbol of tyranny needed to be preserved as a National Memorial to remind our future generations of the tremendous cost that was paid in Indian blood for the freedom of our country”.

In the same year, from their Headquarters at 4, Commercial Building, 23-A, Netaji Subhash Road, Calcutta-1, the Ex-Andaman Political Prisoners’ Fraternity Circle which was an all-India body of the freedom fighters of the Cellular Jail and their family members, wrote a letter to the Prime Minister telegraphed on 30th April 1968 read –

“…Pls issue necessary orders to stop further demolition of Cellular Jail and to start immediate construction of National Monument, refer our representation dated 8th April.” (File no.19).

The Circle represented by Biswanath Mathur, Dr. Bhopal Bose, Ananda Chakravarty, Rakhal Chandra Dey, Benoy Bose, and a few others met the then Prime Minister of India Mrs. Indira Gandhi in New Delhi in April 1968 and requested her to preserve the Cellular Jail as a memorial for the future generations. They appealed to the Prime Minister to stop the demolition of the Cellular Jail.

On 25 May 1968, signal no. 21/10/68-ANI was sent from Home, New Delhi to the Chief Commissioner, Andaman and Nicobar Islands enquiring about the existing status of the jail and some other points. In reply to that Mahabir Singh, the then Chief Commissioner replied vide his signal no. 41-1/68-Home (unclass) dated 27th May 1968 read,

“Kindly refer to your signal on 21/10/68-ANI dated twenty-fifth May regarding the preservation of Cellular Jail (.) The demolition of Cellular Jail was stopped after Home Ministers’ visit in Nov. 1967 and no further demolition has been done. The old dilapidated jail hospital adjoining approach of the hospital is being dismantled as this is necessary to avoid risk of traffic (.) This old dilapidated hospital was not at any time part of the Cellular Jail”.

Subsequently, a pilot team consisting of five members of the Fraternity Circle visited Port Blair on 20-25 March 1969. Again they submitted their representation with the proposal and waited on the PM for this purpose. The proposal was under consideration of GOI as it had the full support of Lal Bahadur Shastri, the then Home Minister who had visited these islands earlier. Eventually, the victory came in the noble hand of the Fraternity Circle. The Government of India on the recommendation of the Fraternity Circle agreed to preserve Cellular Jail as National Memorial.

On 3 May 1969, three wings of Central Tower were declared to be preserved as National Monument, but no concrete step was taken and the whole thing remained on the paper alone. (File 41-1/97-Jail; Acc. No. H (Jail)/812)

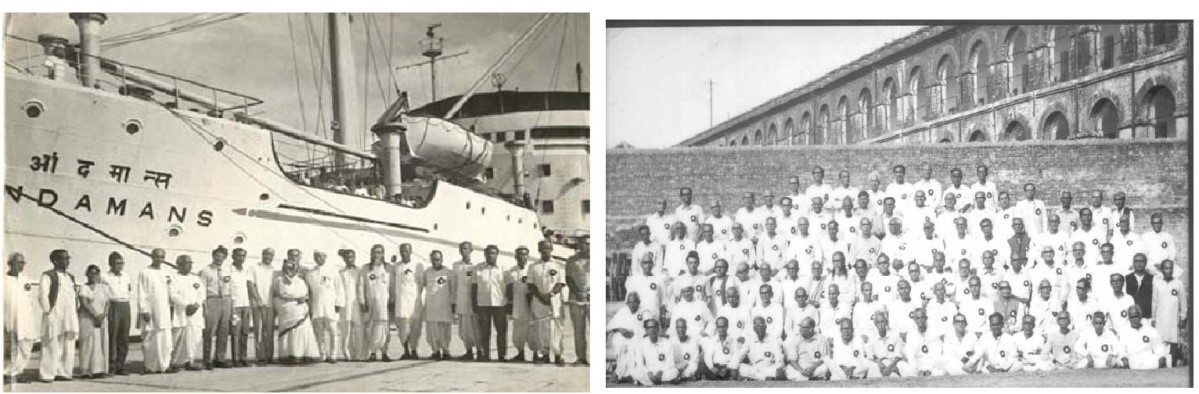

A batch of ‘pilgrim voyagers’ visited Andamans and Cellular Jail in 1975 and they were accommodated at a wooden guest house (now a circuit house namely ‘Teal House’) which was situated at a half kilometer distance from my house at Anarkali, Delaneypur. My grandfather took us there to meet with them and we children touched their feet seeking their blessing. There was also a proposal to allot a plot of land for the construction of a permanent ‘Pilgrim’ Rest House at a suitable place near Cellular Jail. Next year in 1976, Bangeshwar Roy, General Secretary, Ex-Andaman Political Prisoners’ Fraternity Circle, Calcutta deputed 3 batches of ‘pilgrim voyagers’ i.e. Ex-political prisoners who were incarcerated in the Cellular Jail in connection with the freedom movement and the members of their families, each batch consisting of 20 persons to visit Andamans and the Cellular Jail in the month of December 1976 and January and February 1977. The team led by Bangeshwar Roy arrived by the sailing of M.V. Harshavardhana. On 22 January 1977, a dinner was hosted in honour of the freedom fighters in Raj Niwas by the then Chief Commissioner S.M. Krishnatry. They took part in the unveiling of Netaji’s statue on 23rd January 1977. These freedom fighters included a few INA members also.

The Cellular Jail was declared a ‘National Memorial’ after it was inaugurated by Morarji Desai, the then Prime Minister of India on 11 February 1979. Now it is a serious mystery in question why it took more than ten years to inaugurate the Cellular Jail as National Memorial, while the first proposal was submitted in 1967 followed by many other representations, and the same was said to be approved in 1969.

Freedom fighters visiting the Cellular Jail in 1974

With the help of the Ex-Andaman Political Prisoners’ Fraternity Circle, the names of the political prisoners were engraved on the marble plaques in the Central Tower of the Cellular Jail. These marble slabs were delivered by Messrs. Marble Company Importers, 6-Brabourne Road, Calcutta. It was a pure justification with those brave sons of the motherland who languished and some of whom attained martyrdom while undergoing brutalities in solitary confinement in the dungeons of this “horror of horrors” named beguilingly as a jail.

On 30 December 1997, the then President of India K. R. Narayanan felicitated the surviving freedom fighters who were incarcerated in the Cellular Jail and their spouses. It was a momentous occasion during the 50th anniversary of the country’s independence. Thirty freedom fighters out of a total of fifty-three surviving members were felicitated. Thirty-six widows and two relatives of freedom fighters also attended the function. Life-size statues of six martyrs Indu Bhushan Roy, Baba Bhan Singh, Pandit Ram Rakha, Mahavir Singh, Mohan Kishor Namadas, and Mohit Moitra were also unveiled by the President on that day. The President also released on the day a commemorative stamp and a one rupee coin depicting the Cellular Jail.

Thus, the Cellular Jail, hitherto notorious in the British Raj, during the Japanese reign became a grim epicenter or say torture chambers of all the in-human tortures and atrocities during the Japanese occupation of the islands. The saga of the Cellular Jail is not ending in the year 1938 with the final repatriation of the political prisoners. During the Japanese occupation in 1942-45, the Cellular Jail mutely witnessed the human suffering against the various types of inhuman torture along with the well-planned genocidal execution of the innocent population including the INA and IIL members, operated from its cells; and simultaneously the general residents and the freedom fighters had shown the highest degree of courage and patience, besides their marathon struggle. The Cellular Jail’s history of patriotism and of sacrifices in fact goes beyond the timescale of the British reign. It now stands as a glorified and dignified heritage structure of ‘epic human lessons’, illuminating the sung and unsung Andaman history of its heroes.

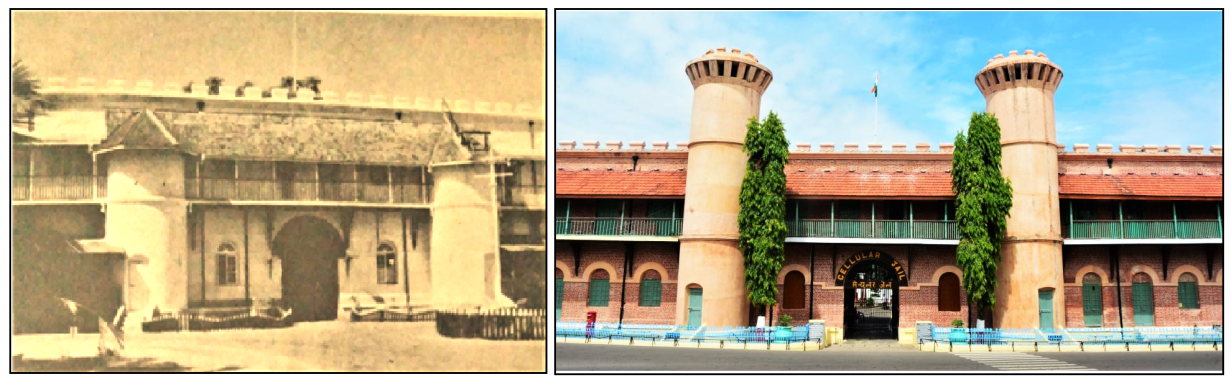

The old (Left) and present (Right) look of the Cellular Jail

Inside view of a Gallery in Cellular Jail

References:

- Brown, A. R. Radcliffe: The Andaman Islanders, The Free Press, New York, 1922.

- Bastille of India, Directorate of Information, Publicity and Tourism, A & Nicobar Administration, 1998

- Ghose, Barindra Kumar, The Tale of My Exile – Twelve years in the Andamans, Arya Office, Pondicherry, 1922.

- Iqbal, Rashida, Unsung Heroes of Freedom Struggle in Andamans (ed.), Directorate of Youth Affairs, Sports & Culture, Port Blair, 2004.

- The Unknown Martyr Diwan Singh Kalepani, Information and Public Relations Department, Chandigarh, Punjab, 1995

- Dictionary of Martyrs - India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947)-Vol. 4 (Ed), Ministry of Culture and Indian Council of Historical Research Government of India, New Delhi, 2016.

- Mazumder, R. C., Penal Settlements in Andamans, Ministry of Information and Publicity, GOI, New Delhi, 1975.

- Report on the Administration of the A & N Islands and the Penal Settlements of Port Blair and the Nicobars for the year 1872-73 to 1874-75, Calcutta, 1875.

- Report on the Administration of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Penal Settlement of Port Blair, Government Printing Press, Calcutta, 1907.

- Report on the Administration of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Penal Settlements of Port Blair and the Nicobars for the year 1872-73 to 1874-75, Government Printing Press, Calcutta, 1875.

- Letters, Prison Sketches and Autobiographical Literature in File 10, A&N Archives, Port Blair, 2005.

- The British Medical Journal, 954, London, April 21, 1906, p. 1.

- The Indian Police Journal, Oct-Dec.2012, Vol. LIX, No.04, New Delhi, pg. 106-108.

- The Telegraph: The Andaman Islands, Brisbane, 10th Jan 1925, 10.

- Antiques and Artefacts of Rajniwas, Department of Art and Culture, A&N Administration, Port Blair, 2019 (Unpublished).

- Personal collection of Eileen Arnell Boomgardt based in the UK.

- Official records in National Memorial (Cellular Jail).

- File No. 21-67, Simla Record, Home Department, Political, GOI, Delhi, 1911.

- File No. 43/82/41-Poll, Political Section, Home Department, GOI, Delhi, 1941.

- File No. 8/8/53- AN, Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI, New Delhi, 1953.

- File No. 164/40-Poll (I) & KW, Home Department, Political, GOI, Delhi, 1940.

- File No. 201, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858

- File No 7/11/33, Home Department, Political, GOI, Delhi, 1933.

- File No. 250, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858.

- File No. 269, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858.

- File No. 317, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858.

- File No. 329, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858.

- File No. 339, Foreign Department, Government of India, 1858.

- File No. 882, (Home Department, Political Branch), GOI, New Delhi, 1922.

- File No. 12014/2A2007-CDN-Arms, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi, 2007.

Andaman &Nicobar Archives, Secretariat, Port Blair

- File No. 41-1/68-House).

- File-41-1/68-House; archives H 901.

- File no. 21-21/51 of 1951, ACC. H-76.

- File 41-1/97-Jail; Acc.No. H (Jail)/812.

- Documents donated by MA Mujtaba (Vol.1-2).

- Extract from Andaman & Nicobar Manual - Section 40-46.

- File No. 1.

- File No. 1-3(1)-45 (Acc. A/134).

- File No 1/5/53 (Acc. J/141).

- File No 1/5/54 (Acc. J/151).

- File No. 1-35-46 F.

- File No. 1-36/47 Vol.2(Home 23-A).

- File No. 1-41-46-CC (Acc. J/2 Judicial/Revenue Section).

- File No. 1/41/49/50 Main 1949/50 (Acc. J/124 Judicial/Revenue Section).

- File No. 1-47/45.

- File No. 1-81/53 (Acc. J/143-1953).

- File No. 1-93-46 (Home Section).

- File No. 1-108/46.

- File No. 1/110/46.

- File No. 1-130/47.

- File No. 1-154/46.

- File No. 1/172/46 (Home Section).

- File No. 1-454/84-TW.

- File No. 1-636/50 (Viper).

- File No. 1-732/50 (Archives - J/128A).

- File No. 1-732/52 (Vol.1).

- File No. 1-732/52 (Vol.2) (Acc. J/136).

- File No. 1-732/51 (Acc. J/133A).

- File No. 1-946/49 (H - 52).

- File No. 2-19/66-RH (Colonization in Andamans).

- File No. 2-67/65-J (Netaji Club).

- File No. 9 (Cellular Jail).

- File No. 10-16/49-52 A (Acc. J/23 Judicial/Revenue Section) (1949 Batch).

- File No. 11-4/48 (Acc. J/17A Judicial/Revenue Section) (Bhantus).

- File No. 11-36/51 of 1951 (Home Section).

- File No. 12 (Freedom Fighters deported to Andamans).

- File No. 12-2 (S)/5/1954.

- File No. 12-16-46 (Acc. J/4A Judicial/Revenue Section) ( Deaks).

- File No. 15-259/70(J.I) (Land for Homfraygunj Memorial).

- File No. 16.

- File No. 19.

- File No. 19-4/59-PQ (RH) J.I (Acc. J/216 A).

- File No. 19-4/59/PQ (RH) J.I (Acc. J/216).

- File No. 19-4/74/PQ (Acc. J/480).

- File No 21-2-1945 (Home) (Acc. 4).

- File No. 21-2(1)45 (Pension papers of J.J. Delaney).

- File No. 21-3/50 (H-65) (1941 Earth Quake).

- File No. 21-21/51 (Escape of Prisoners from Cellular Jail).

- File No. 21-2(1)/ 45 (Home Section).

- File No. 27-3/50 of 1950 (Home Section).

- File No 29-6/55 (Archives-J/170A) (Refugee Misc./Rajani Ranjan Sarkar).

- File No. 31.

- File No. 31-1/82 H&R.

- File No. 33-21/71-Jud-I (Acc. J-1190) (Allotment of land at Tirur).

- File No. 34.

- File No. 34-190/90 H.

- File No. 41-1/97- Jail.

- File No. 41-14/98-Home (Jail) (Convicts in Jail).

- File No. 41-35/69-Home (Acc. H/988, Category ‘A’).

- File No. 41-46/76- Home (Acc. Jail/675-A).

- File No. 41-76/79- Hom

- File No. 42-1(Viper).

- File No. 42-20/Rev/95-95/Part File No III.

- File No 51/3/45 – Jails.

- File No. 51-26/45 Jails (Home).

- File No. 51/39/45 Jails (Home), (Note of S.M. Sandak).

- File No. 55/6/45-Jails (Acc. J/113 Judicial/Revenue Section).

- File No. 55/9/45 Jails (Home).

- File No. 55/47/45 Jails (Home).

- File No. 55/48/45 Jails (Home).

- File No. 55/58/45 Jails (Home).

- File No. 61-7/67 –Pub.

- File No. 64-191/60-Pub (Acc. H/551-B).

- File No. 64-272/62 - Pub (H 253-A).

- File No. 67 (the Andaman Islands under Japanese Occupation -1942-45 by Ramakrishna).

- File No. 69 (Andaman after Reoccupation by R. Shyamji Krishna-1946).

- File No. 78/30/42- Jails, Acc. A/28 (Shrimati Inder Kaur, wife of Dr. Diwan Singh).

- File No. 84 (The Refugees in Andamans).

- File No. 104-20 (Ross).

- File No. 106 (Rehabilitation).

- File No. 111- 72/68 – Admn (PF)(2)-1968 (Acc. J/752 ) (Rajani Ranjan Sircar).

- File No. 173-84/62-G-1961.

- File No. 1945 (Acc. A/127).

- File No. H-901.

- File No. J/63 A.

- File No. J/128 A.

- File No. J /170A (Refugee Misc).

- File No. J/221.

- File No. J/732/50.

- File No. J/732/51 (Acc. J/133A).

- File No. J/752 (Home).

- File No. J/1724, (Home).

- File No. J/1738, (Home).

- File No. J/1761, (Home).

- File (Revenue/Jail) Acc. 2549.

- File (Revenue/Jail) Acc. 2800.

- File (Revenue/Jail) Acc. 2424.

- Letter dated 22-10-1945 from Littleworth to Chief Commissioner (Design), Port Blair.

- Letter dated 03-12-1945 from N.K. Paterson, Chief Commissioner, Port Blair to Mrs. Nell Spencer.

- Letter dated 10-12-1945 from Littleworth to Chief Commissioner, Port Blair.

- Letter dated 20-12-1945 from Commandant & Superintendant of Police to Chief Commissioner.

- Letter No 816 dated 24-01-1946 from N.K. Paterson, Chief Commissioner to Mrs. Nell Spencer.

- Letter No 6-102/51 dated 03-03-1951 from Chief Commissioner to Secretary to GOI, New Delhi-2.

- Letter dated 26-11-1953 from Superintendant of Cellular Jail to Secretary to Chief Commissioner.

- Letter dated 21-03-1958 from Durga Parshad, Retired Forest Officer to Chief Commissioner (Acc. J/54 Judl/Rev Section).

- Letter No 12276/13/19/60 dated 16-06-1960 from Superintendant of Police, Port Blair to Chief Inspector of Explosives in India, GOI, Department of Explosives, Nagpur.

- Letter No 49879/K3/66/RD dated 08-12-1966 from the Secretary to Government of Kerala to Secretary to GOI, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi.

- Proclamation No 7 dated 7th February 1946 by Louis Mountbatten.

Dr. Pronob Kumar Sircar, writer of this research based blog is an ethno-historian based at Port Blair.