In the year 1857, Delhi, or the erstwhile Shajahanabad, witnessed one of the most significant uprisings against British colonial rule in India. This historical event, often referred to as the 'Indian Uprising of 1857' or the 'First War of India's Independence,' left an indelible mark on the history of the subcontinent. Among the affected regions, the city of Delhi, the then seat of Mughal power, was a crucial centre of resistance as it witnessed brutalities that deeply impacted its infrastructure and the lives of its inhabitants. Robbery, plunder, and murder became an everyday occurrence in Delhi, and it is generally estimated that around 27,000 people were hanged or shot in Delhi during this period of turmoil.

Stamp commemorating 1857 uprising

The 1857 Uprising was a watershed moment in Indian history and had far-reaching consequences that could not be limited to political and economic disorder. Delhi, which was also a centre of literature and culture, was deeply affected. During that time, the residents of Delhi, especially poets and writers, used the Urdu language as a medium to historicise atrocities and human emotions.

However, first, it is essential to take note of Urdu's development in Delhi as a language of literary expression. By the 19th century, Urdu had emerged in Delhi as a highly developed language of poetry and a medium to inculcate values and learning. Urdu inspired a great love of fine writing and literature. It was believed to have the ability to say a lot in a few words and accommodate every human emotion. The diversity of themes represented in various Urdu ghazals (poetic forms composed of rhyming couplets), namz (poetry), marsiya (elegies), qissa (narrative poem), and stories enable us to trace Urdu's vibrant character.

The historical and political ruptures from the late 18th - 19th century, or the diminishing glory of the medi city of Shahjahanabad (Delhi), inevitably shaped contemporary Urdu literature. Urdu poets in Delhi or those who migrated from Delhi expressed their grief at the decline of the Mughal Empire and produced some first-hand historical accounts.

The beloved capital, Delhi, became a favourite subject of Urdu poets leading to a category called Dabistan-e Dihli, i.e.' the Delhi School of Poetry.' Further, the Urdu poets also used traditional genres such as the shahr ashob (city disturber) to describe the political, economic and social disturbances. Amongst the numerous categories, some poets have directly used the word Delhi; there are poems in which Delhi is used as a metaphor, while some poets have described Delhi's social life satirically.

Eminent Urdu poets, like Mirza Ghalib, have extensively used Urdu to express their inconsolable feelings over the destruction of Delhi. The literary works of Mirza Ghalib are based on themes that range from love, longing, and desire to history and nationalism.

Stamp of Mirza Ghalib

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869) is believed to be one of the most remarkable person in Urdu's literary landscape. He was of Turkish descent and a resident of Shahjahanabad's (Delhi) neighbourhood called Bazaar Balimaran. Ghalib was the court poet of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, and he was deeply rooted in the city's culture, language, and history. He followed no profession except writing poetry and other literary works. Although from an aristocratic lineage, Ghalib remained perpetually in debt due to his extravagant habits.

Mirza Ghalib is both an important historical and literary figure who witnessed the Great Revolt of 1857. His writings vividly describe the British re-occupation and the destruction of his beloved city. The ruthlessness with which the great cultural capital was destroyed has been eloquently covered in his literary works, such as Dastambu (Ghalib's Persian journal), Urdu-e-Mualla, Ud-e-Hindi, Insha-e-Ghalib, and Khutut-e-Ghalib.

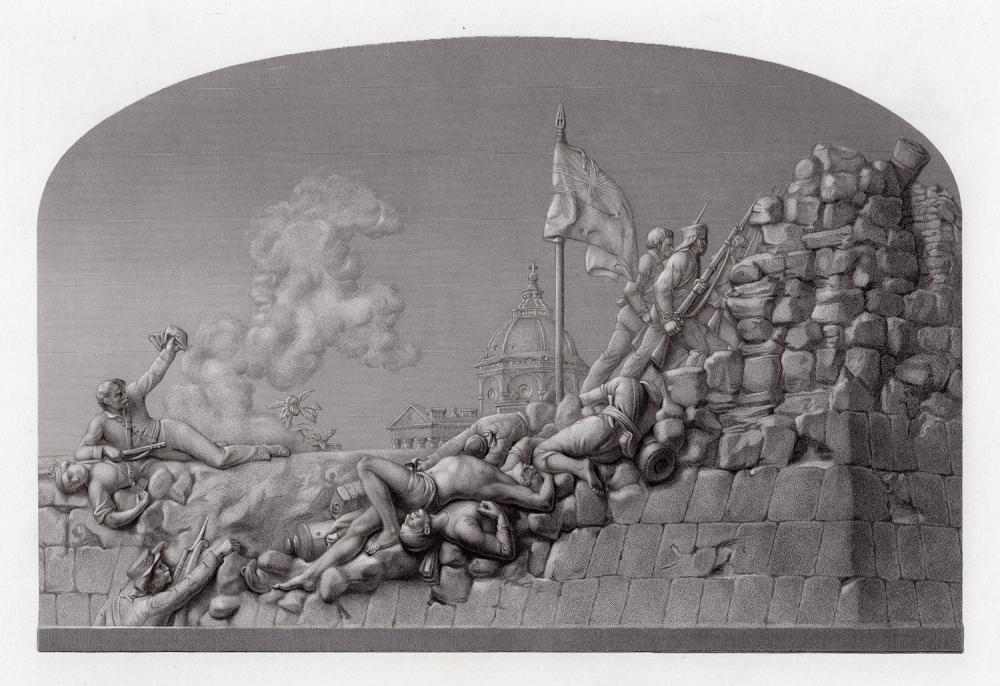

Loss of lives at the battle of Kashmere Gate, 1857

Ghalib has used Urdu as a powerful medium to express the sentiments of resistance, resilience, and the yearning for freedom. Further, in some of his letters, he wrote with great boldness about Delhi's deteriorating situation, wherein the area between Cashmere (Kahmiri) Gate and Chandni Chowk became a battleground due to fierce encounters between the British Army and the freedom fighters. At the same time, the Indian sepoys occupied the Ajmeri, Turkman, and Dilli gates. Ghalib mourned the ravaged streets, the crumbling monuments, and the loss of the city's once-vibrant spirit. He wrote, 'Here in this city with my wife and sons, I am swimming in a sea of blood.'

After the British regained control of Delhi and the Red Fort, the residents, especially Muslims, were under severe pressure. They were expected to pay a fee or obtain a permit to enter the city, which was once their home, the bazaar (marketplace) became a slaughterhouse, and houses became prisons. Ghalib ridiculed this unjust situation by writing that “the government, of course, decides how much you will have to pay. They ruin you, but they say you are settled again.” Days of misery were followed by the Uprising, and Delhi's residents were deprived of basic necessities such as candles, leaving the houses dark at night.

The Great Revolt disassociated Ghalib from his friends, relatives, and students who were either murdered, reprimanded by the British, or left Delhi after the ruin of their families. The house of his two close associates, Nawab Zia ud-Din and Amin ud-Din, was ransacked by British looters, their residence also housed a library consisting of Ghalib's Persian and Urdu works. Therefore, 1857 was not just a period of political turmoil but also a period wherein India lost a huge corpus of Urdu literature.

Ghalib writes in Dastambu that the tragedies of 1857 inflicted incurable wounds on him and his city (Delhi). He has used some of the harshest terms to describe the Uprising, like rustakhez-e-beja i.e., the ultimate resurrection, fasad (destruction), and fitna (evil, conflict). At another place in Dastambu, he states that “the heart is not a piece of iron or stone; how can it not be full? The eyes are not a hole in a stone wall that do not shed tears. One must grieve over the deaths of rulers, and weep for the destruction of India.”

The piteous condition of Delhi brought tears to his eyes. Delhi looked to him as a soulless and dead city whose royalty and nobility were destroyed and whose residents were driven like sheep, homeless, harassed, and beaten. In a poem on Delhi's lurid condition, Ghalib wrote:

Now every soldier that bears arms

Is sovereign, and free to work his will

Men dare not venture out the street

And terror chills their heart within them.

Their homes enclose them as in prison walls

And in the Chauk the victors hang and kill

The city is athirst for Muslim blood

And every grain of dust must drink its fill.

Even before the destruction in Delhi, Ghalib's private letters to friends in Oudh described his deepest feelings against the ruthless Britishers. Therefore, along with poetry, his personal or confidential letters regarding Delhi and other princely states are also indispensable aspects of the Uprising's history. Unlike Dastambu, he had written with more intensity, depth, and freedom in his letters.

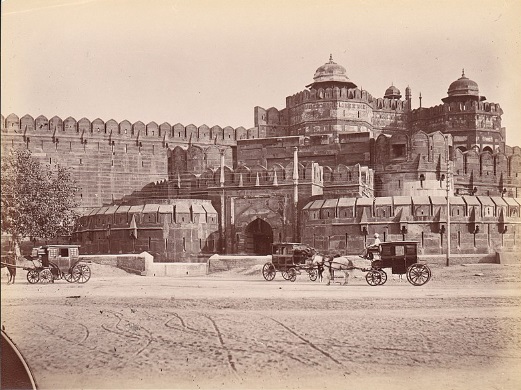

Red Fort in 1857

Nostalgia and longing for the bygone era were prominent themes of Ghalib's writings, which intend to remind readers of Delhi's past grandeur. He wrote that life in Delhi depended before the Uprising on five things: the Red Fort, Chandni Chowk, the daily assembly at the Jama Masjid, the weekly stroll along the Jamna (Yamuna) bridge, and the annual gathering of the flower sellers. Ghalib has pointed out very strongly about British excesses and cruelties, as he mentioned that the attack by the British army destroyed life, wealth, honour, property, and indeed, all the signs of life in Delhi. After the Uprising, gallows were put up all over Delhi, and the suspected citizens were hanged.

However, in the after of the 1857 Uprising, these things not only disappeared from Delhi but also took away the city's character. Delhi was tragically transformed from being a thriving metropolis to a military camp. The royal orchards in Red Fort were turned into horses' stables, and the royal residence became British billets. Ghalib has further compared Delhi without its rulers with a garden without a garden and full of fruitless trees.

Between 1857- 58, Ghalib remained a suspect in British eyes. He very circumspectly wrote, “If we are still alive and can meet again, the story will be told. Otherwise, the story is over. I am afraid to write.” It is believed that Ghalib's financial condition deteriorated to the extent that he had to sell his household items to survive. He has described his impoverished situation as 'I now see no way of getting back the pension I once had from the British. I'm carrying on by selling my bedding and clothing; other people eat bread, I eat clothing.' Even his wife's jewellery was lost during the disturbances which further aggravated his frustration.

The Urdu literature related to the 1857 Uprising is both a historical and emotional account of Delhi's residents. Ghalib's works vividly depict the destruction and desolation that befell Delhi during the 1857 Uprising; he has eloquently captured the anguish and grief of Delhi's residents during this tumultuous period and wrote with greater boldness and freedom.

Ghalib was an ambitious writer, and throughout his life, he made efforts to fulfil his desires for a high position and respectability. Only in May 1860, his pension was restored through the efforts of Nawab of Rampur, but Ghalib's dream of being the Poet Laureate was never fulfilled. Ghalib has gone to the extent of calling the British 'monkey' as he wrote, “Well done O Monkey, this violence inside the city.” For him, the 1857 Uprising and the events that followed breached Delhi's order and ruined the great cultural capital. Overall, Urdu literature has extensively captured the struggles witnessed during the 1857 Uprising, and this political event enlarged its domains of from etiquette and romance to the language of lament, struggles, and nationalist sentiments.

Source: Indian Culture Portal